Armenia

Jump to: Ani (capital of the Armenian Bagratid kingdom from 953 to 1045 AD, now in Turkey)

Jump to: Ashtarak

Jump to: Echmiadzin

Jump to: Gerhard Monastery

Jump to: Haghbat

Jump to: Khor Virap Monastery

Jump to: Spitak

Jump to: Yerevan

the country

the flag

Armenia (country),

republic in western Asia, bordered by Georgia on the north, Azerbaijan on the

east and the Azerbaijani exclave of Naxçývan (Nakhichevan’) on the

southwest, Iran on the south, and Turkey on the west. With Georgia and

Azerbaijan, Armenia is located in Transcaucasia (the southern portion of the

region of Caucasia), which occupies part of the isthmus between the Black and

Caspian seas. Yerevan is the capital and largest city.

In Armenian, the official state language, Armenia is named Hayastan.

Ethnic Armenians, who call themselves Hay, constitute more than 90

percent of the country’s population. Incorporated as a part of the Union of

Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1922, Armenia became independent in 1991.

Its first post-Soviet constitution was adopted in 1995.

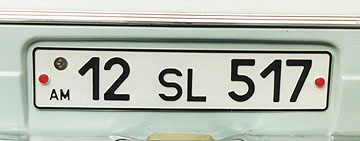

small manufacturer

Armenia occupies about 29,800 sq km (about 11,500 sq mi) of the northeastern

portion of the Armenian Highland, an extensive upland area that extends as far

south as Van Gölü (Lake Van) in Turkey. Armenia is extremely mountainous. The

average elevation is about 1800 m (about 5900 ft). Mount Aragats is the highest

point in the republic, reaching a height of 4090 m (13,419 ft). Mountain ranges

in the republic include the P’ambaki, Geghama, Vardenis, and Zangezur branches

of the Lesser Caucasus (Malyy Kavkaz) mountain system.

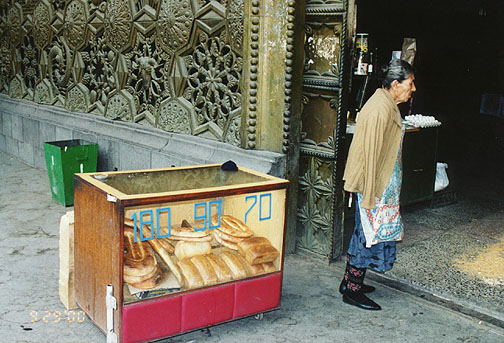

bread for sale

Armenia is the only landlocked country in Transcaucasia. The republic contains many mountain lakes, the largest of which is Lake Sevan, located in the northeast. Lake Sevan is the largest lake in Transcaucasia and one of the largest high-elevation lakes in the world. It is also a popular resort area. In the early 1990s the lake’s wildlife habitat was threatened, as large amounts of water were being taken from Lake Sevan to supply hydroelectric plants. A tunnel was constructed to bring water from the Arpa River into the lake in order to maintain a constant water level. Although many rivers flow into Lake Sevan, the main outlet is the Hrazdan River, which flows south to join the Aras (known in Armenia as the Arax) River, Armenia’s largest and longest river. The Aras originates in the mountains of northeastern Turkey and flows generally eastward, following Armenia’s border with Turkey and then Iran, until it turns north to join the Kura River in Azerbaijan. Armenia contains a dense network of small rivers and streams that are part of the Aras-Kura river basin. Due to the mountainous terrain, waterfalls and rapids are common.

Bus using

natural gas a fuel

(note multiple gas tanks on roof)

Armenia’s plant life is diverse. In the semidesert regions, which occupy the lowest elevations, drought-resistant plants such as sagebrush, juniper, and honeysuckle are common. Grasses predominate in the steppes, which are higher in elevation and constitute most of Armenia’s terrain. Beech and oak trees are found in the forest zones of the extreme northeast and southeast. Animal life in Armenia includes wild boars, jackals, lynx, and Syrian bears.

The population of Armenia is 3,433,629 (1997 estimate), giving the country’s land area a population density of 115 persons per sq km (298 per sq mi). Armenia is highly urbanized, with 69 percent of all residents living in cities or towns. Population is concentrated in river valleys, especially along the Hrazdan River, where Yerevan, the capital and largest city, is located. Armenia’s second-largest city is Gyumri (formerly Leninakan), the site of a devastating earthquake in 1988.

Armenia was the most ethnically homogeneous republic of the 15 republics that made up the USSR, and the country is still characterized by a high degree of ethnic homogeneity. Ethnic Armenians, or Hay, constitute more than 90 percent of the population. Kurds and Russians are the next two largest ethnic groups in the republic, each making up less than 2 percent of Armenia’s total population. Small numbers of Ukrainians, Assyrians, Greeks, and Georgians also live in Armenia. Azerbaijanis were the largest minority group during the Soviet period, but in the early 1990s nearly the entire Azerbaijani population fled or was forcibly deported from Armenia because of ethnic tension brought on by a secessionist conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, a region inhabited predominantly by Armenians in western Azerbaijan. In the reverse direction, many Armenian refugees entered Armenia from Azerbaijan during the conflict.

Armenia’s official state language is Armenian, a distinct Indo-European language. It has a 38-letter alphabet that was derived from the Greek alphabet and dates from the early 5th century. Of its many spoken dialects, the most important are Eastern or Yerevan Armenian (the official language) and Western or Turkish Armenian (see Armenian Language). Armenia’s ethnic minorities also speak their own native languages, mainly Russian and Kurdish.

Armenians were converted to Christianity in the early 4th century, and by some accounts they were the first in the world to adopt Christianity as a state religion. During centuries of foreign domination, when Armenians did not have a state of their own, the Armenian Church helped maintain a sense of collective identity. When Armenia was part of the Russian Empire, the head of the church, known as the catholicos, was considered the most important representative of the Armenian people. The church therefore developed as a strong symbol of the Armenian nation. The Armenian Church was allowed to continue as the national church of the Armenian republic during the Soviet period, although the Soviet Union was officially atheistic because of its Communist ideology. Soviet authorities granted official recognition only to Armenian clergy who were affiliated with a pro-Soviet political faction. Clergy who supported nationalist groups were not allowed to hold power in the church. Today, Christianity remains the country’s predominant religion. Most ethnic Armenians belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church. Among ethnic minorities, there are Russian Orthodox Christians, Protestants, and Muslims.

commemorating Armenia as a Socialist Republic

As a result of the Soviet government’s emphasis on free and universal education, nearly all adults in Armenia can read and write. During the Soviet period, the educational system was controlled by the central government in Moscow, and schools were required to promote Soviet Communist ideals. In the early 1990s, after achieving independence, Armenia made substantial changes to its educational system. Most notably, curricula began to emphasize Armenian history and culture, and Armenian replaced Russian as the dominant language of instruction. Today, primary and secondary levels of instruction are compulsory and available free of charge. The country’s largest university is Yerevan State University, founded in 1919 in Yerevan. Other institutes of higher education offer specialized instruction in engineering, agriculture, architecture, fine arts, and theater arts.

Armenians typically maintain close family ties and pride themselves on their distinctive cultural traditions. Armenian music and cuisine are similar to those of the Middle Eastern countries. On festive occasions, Armenians enjoy traditional folk music and circle dances. Spectator sports such as basketball, soccer, and tennis are popular, and in international competitions Armenians have excelled in wrestling, boxing, and gymnastics. Armenians also like to play chess and backgammon in their leisure time. Most city-dwellers live in apartment buildings that were built during the Soviet period; many of these are now dilapidated. Rural residents live mostly in single-family houses, and many members of an extended family often live together. Family and friends are the center of social life, and respect for elders links generations.

women selling food they prepared

Art that was distinctively Armenian in form first emerged in the early 4th century, coinciding with the introduction of Christianity in the country. Religious icons were a favored subject during that time. Armenia subsequently had three major artistic periods, which coincided with periods of independence or semi-independence. These periods occurred from the 5th century to 7th century, during the 9th and 10th centuries, and from the 12th century to the 14th century.

Armenian folk arts, which have remained essentially unchanged for centuries,

include rug weaving and metalwork. The carving of decorative stone monuments

called khatchkars is an ancient Armenian art form that continues to be

practiced today.

An Armenian literary tradition first emerged in the 5th century. Literary themes were at first historical or religious, as represented by two great works of the period, the History of Armenia, by Movses Khorenatsi, and Eznik Koghbatsi’s Refutation of the Sects. The first great Armenian poet was the 10th-century bishop Grigor Narekatsi, whose mystical poems and hymns strongly influenced the Armenian Apostolic Church.

A secular, or nonreligious, literary (and musical) tradition began to develop in the 16th century with the appearance of poet-minstrels called ashugh, whose lyric poems were written and performed in the vernacular language. Many ashugh love songs remain popular to this day.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries several Armenian writers gained attention for their modern novels, short stories, and plays. The most renowned novelist of this period was Hakob Melik-Hakobian, who is best known by his pen name, Raffi. His novels include Jalaleddin (published in 1878), Khent (1880), Davit-Bek (1881-1887), and Samuel (1888). In the 1920s the Communist regime of the Soviet Union instituted a policy of cultural uniformity, known as socialist realism, which largely stifled Armenian literary development. Armenia’s first great composer of classical music, internationally famous Aram Ilich Khachaturian, wrote his masterpieces during the Soviet period. Some of his works reflect the influence of Armenian folk music.

after the

collective farms collapsed

plots of orchards were given to individual farmers

providing a wealth of fruit in the market

favorite snacks

Museums in Armenia include the Armenian State Historical Museum, the Armenian State Picture Gallery, and the State Museum of Literature and Art, all in Yerevan. The city is also the site of the State Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet. A national dance company and several orchestras tour throughout the country.

Armenia’s constitution was approved by referendum in July 1995, replacing the 1978 constitution of the Soviet period. It declares Armenia to be an independent democratic state and guarantees the protection of basic human rights and freedoms. All citizens age 18 and older may vote.

The new constitution gave the president, who is head of state, broad executive powers. He or she is elected by direct vote for a term of five years and may serve no more than two consecutive terms. The president appoints the prime minister, who presides over the council of ministers. The council’s members are appointed by the president upon the recommendation of the prime minister.

Armenia’s parliament, called the National Assembly, is a unicameral (single-chamber) legislative body. The National Assembly is composed of 190 members who were elected in 1995 for four-year terms under a mixed system of direct vote and proportional representation. Under the 1995 constitution, the National Assembly is to be reduced to 131 members, all of whom are to be directly elected for four-year terms. These provisions are supposed to go into effect for the next parliamentary election, scheduled for 1999.

Armenia’s 1995 constitution provides for an independent judiciary. The highest appellate court is the Court of Appeal, which ensures uniformity in how the country’s laws are applied through its final review of cases. The Court of Appeal’s members are nominated by the Council of Justice, an administrative body created to ensure independence of the courts, and then appointed by the president. Armenia also has a Constitutional Court, which is charged with ensuring that legislative decisions and presidential decrees are consistent with the constitution. Of the Constitutional Court’s nine members, five are appointed by the president and four by the National Assembly. The president of Armenia heads the Council of Justice. The minister of justice and the prosecutor general serve as deputy heads of the council.

![]()

Making of lavash

dough is placed on board

spread out in a thin layer

placed in hot oven and baked

![]()

For purposes of local government, Armenia is divided into ten marz (regions), including Yerevan. The regions are subdivided into hamaynk (communities). The National Assembly appoints and dismisses governors to administer the regions in accordance with national policies. The communities exercise local self-government. They hold local elections every three years to select a community leader.

Armenia’s constitution guarantees a multiparty political system, but the activities of political parties must not violate the constitution or the law. The Republican bloc, an alliance of six moderate nationalist parties led by the Pan-Armenian National Movement (PNM), won an overwhelming majority of seats in the parliamentary elections of 1995, thereby retaining the PNM’s dominant position in government. Other parties with representatives in the National Assembly are the Shamiram Women’s Party, the Communist Party of Armenia, the National Democratic Union, the Union for National Self-Determination, and the Liberal Democratic Party.

country is rich in fruit

The PNM-led government barred nine opposition parties from participating in the parliamentary elections. Armenia’s leading opposition party, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF; also known as Dashnaks, a shortened version of its name in Armenian), was officially suspended in December 1994. One ARF member who ran without official party backing nevertheless succeeded in winning a parliamentary seat. The ARF again became a legal party after the fall of President Levon Ter-Petrosyan in February 1998.

Armenia is a member of the CIS, the United Nations (UN), and the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). In October 1994 the country joined the Partnership for Peace program, which provides for limited military cooperation with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Photos of an Armenian Church on an island in Lake Van

HISTORY

This section highlights some of the pivotal events in the history of Armenia.

For a more detailed history of Armenia before the 20th century, see

Armenia (region).

The modern republic of Armenia covers only the northeastern portion of an area historically inhabited by Armenians, whose ancestors settled in the area of Mount Ararat, in present-day Turkey, in the late 3000s BC. In the early 1st century BC Armenian king Tigranes the Great formed an empire—the most extensive Armenian realm in history—that stretched from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea and included parts of Georgia and Syria. Tigranes’ empire came under the control of the Roman Empire before the end of the 1st century, however, and Armenia became a buffer zone—and often a battleground—in Rome’s campaigns against the Parthians, who ruled over Persia (present-day Iran).

In the 1st century AD a Parthian-Roman treaty installed the Parthian Arsacid dynasty as rulers of Armenia. The treaty required the dynasty to act in allegiance with Rome. In Persia, the Arsacid dynasty fell to the Sassanids in the early 3rd century. The Sassanids initially seized Armenia, but the Roman Empire wrested control of Armenia later that century and then restored the Arsacids to power, crowning Tiridates III as Armenian king. Tiridates converted to Christianity in the early 4th century and established a state church. His conversion predated that of Constantine the Great of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern portion of the Roman Empire), making Armenia the first state to officially adopt Christianity.

early

churches were cut into rock

(distinctive interior roof design carved into the rock)

detail

The Byzantine and Persian empires divided Armenia in the late 4th century, with Persia taking the larger eastern section, but in the early 7th century all of Armenia came under Byzantine rule. In 653 the Byzantine Empire ceded Armenia to the Arabs, who had already conquered Persia. Armenia was granted virtual autonomy under Arab suzerainty. In 806 the Arabs installed a noble Armenian family, the Bagratuni (Bagratid) line, as governors of Armenia. In 885, one of this line, Ashot I, became the sovereign of an independent Armenian kingdom, and several additional small independent Armenian kingdoms subsequently arose. This period of Armenian independence ended with the conquests of a resurgent Byzantine Empire under Basil II, who ruled from 976 until 1025. Byzantine control was short-lived, however, as invasions of the Seljuk Turks (see Seljuks) brought most of Armenia under Turkish control by 1071.

In the 13th century Armenia fell to the Mongols, who continued to rule until the early 15th century. The Ottoman Empire conquered most of Armenia in the 16th century, although Iran (formerly Persia) continued to hold some Armenian lands. During the next several centuries, these two powers vied for control over Armenia.

A Russian Conquest and Ottoman Rule In the early 19th century Russian expansionism extended into Caucasia. By the late 1820s the Russian Empire had gained control of Iran’s territories in Transcaucasia. The area of present-day Armenia thereby became part of the Russian Empire, while the rest of historic Armenia remained part of the Ottoman Empire. A large number of Armenians subsequently migrated from the Ottoman Empire to Russian-held territory.

During the late 1800s Armenian political groups formed and began agitating for greater levels of autonomy for Armenians, at times resorting to terrorism. One party, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, or ARF (commonly called Dashnaks), sought autonomy for Armenians within the Ottoman and Russian empires. The Hunchak ("Bell") party called for an independent socialist Armenia. The Ottoman and Russian governments responded to the demands of Armenian nationalists with repressive measures. Ottoman forces systematically massacred hundreds of thousands of Armenians between 1894 and 1896. The Russian government, although not as repressive as the Ottoman government, closed Armenian schools and ordered the confiscation of church property. Armenian nationalists led an armed resistance against the seizure of church property until Russia put a stop to the practice in 1905.

Armenian Genocide Memorial

The worst atrocities against Armenians occurred in the Ottoman Empire during World War I (1914-1918), when widespread massacres of Armenians were sanctioned by the Ottoman government of the Young Turk era. The Ottoman government accused the Armenians of being pro-Russian and cited the threat of internal rebellion as justification for the massacres. The Ottoman government also ordered massive deportations of Armenians from their homelands in Ottoman-held territory mainly to the deserts of present-day Syria. Many Armenians perished from starvation and disease or were killed by Ottoman soldiers during the forced marches. Although Russian and European powers protested the genocide, they did not intervene, and the Armenians succumbed with little organized armed resistance. By the time World War I ended, more than 800,000 Armenians had died. The massacres continued into the early 1920s. During the genocide many Armenians escaped to other countries, including Russia and the United States. By 1923 Anatolia was nearly emptied of its Armenian population.

the eternal flame

Russia conquered the greater part of the Ottoman-held Armenian lands in 1916, during World War I. However, after the Bolsheviks (militant socialists) seized power in Russia during the Russian Revolution of 1917 and withdrew Russia from the war, the Ottomans reoccupied their lost territories. The collapse of the Russian Empire during the revolution helped galvanize popular support among Armenians for the nationalist agenda of the ARF. In May 1918 the ARF proclaimed an independent Armenian state that encompassed most of the Armenian lands included in the former Russian Empire. Armenia fought short and ultimately unsuccessful wars against Georgia and Azerbaijan in an attempt to secure predominantly Armenian-inhabited territories, such as the region of Nagorno-Karabakh held by Azerbaijan.

In the August 1920 Treaty of Sèvres between the Ottoman Empire and the World War I Allies, the Ottoman government agreed to the partitioning of the empire and recognized Armenian independence. Meanwhile, however, Turkish nationalist leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had reunited the Turkish national movement in the Ottoman lands and had set up a provisional government in Ankara. In September the new Turkish government rejected the Treaty of Sèvres and invaded Armenia. The Bolsheviks also invaded Armenia, thereby preventing the Turkish troops from establishing full control over the country.

Armenian nationalists entered a political agreement with the Bolsheviks in December 1920, forming a new coalition government that then proclaimed Armenia a socialist republic. In an agreement signed the same month, Bolshevik-controlled Azerbaijan agreed to make the territories of Naxçivan and Nagorno-Karabakh part of Armenia. In early 1921 the Bolsheviks took complete control of the government, expelling the Armenian nationalists. Together with Georgia and Azerbaijan, which had also come under Bolshevik control, Armenia was incorporated into the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (SFSR) in March 1922. In December the Transcaucasian SFSR became one of the four original republics of the Bolsheviks’ new state, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Despite the earlier agreement, the Soviet authorities placed the territories of Naxçivan and Nagorno-Karabakh under Azerbaijani governance.

The new Soviet Communist regime sought to neutralize nationalist sentiment in Armenia. The ARF was outlawed in 1923, and the Armenian Communist Party was the only party allowed to function. Leaders of the Armenian Church were persecuted, churches were closed, and church property was confiscated. Beginning in the late 1920s many Armenian nationalists and others suspected of opposing the Soviet regime were executed or deported to labor camps. The purges intensified in the mid- and late 1930s, when the Great Purge masterminded by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin extended throughout the entire Soviet Union. Also in the mid-1930s the Soviet regime banned literature by 19th-century Armenian authors, such as Hakob Melik-Hakobian (pen name, Raffi).

The Soviet regime also implemented policies to fully integrate and centralize the economy of the Soviet Union. Armenia soon became one of the USSR’s primary sources of copper. During the 1930s new industries such as chemical-manufacturing plants were rapidly introduced in Armenia, while private farms were forcibly combined into large state-owned farms. The collectivization of agriculture met with fierce resistance among the peasantry, which initially slowed the process. By 1936, however, the revolts were largely subdued by force. That year the Transcaucasian republic was dismantled, and Armenia became the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) within the USSR.

Soviet authorities began to allow some leniency in the cultural sphere during World War II (1939-1945). The Communist government, although officially atheistic, called upon the Armenian Apostolic Church to rally the Armenian people behind the Soviet war cause. Some expressions of nationalism were tolerated, especially after the death of Stalin in 1953. However, substantial political and social reforms did not take place until several decades later.

In the mid-1980s Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced glasnost’

(Russian for "openness"), a reformist policy that allowed

controversial issues to be discussed publicly for the first time in Soviet

history. Armenians initially took advantage of glasnost’ to demonstrate

against the environmental problems in their republic. Historical and political

grievances then became the focus of public unrest. In February 1988 crowds of as

many as one million people took to the streets in Yerevan to rally for Armenia’s

annexation of the Azerbaijani region of Nagorno-Karabakh, where the

predominantly Armenian population had already begun a secessionist movement.

In December 1988 northern Armenia was devastated by an earthquake that killed

25,000 people and left more than 400,000 homeless. Government relief efforts

were slow and badly organized. The arrival of essential supplies such as fuel

was delayed by an economic blockade Azerbaijan had imposed on Armenia in 1989

because of the war in Nagorno-Karabakh. The war also hindered efforts to

reconstruct Armenia’s earthquake-damaged infrastructure.

Toward the end of 1989 the Armenian Supreme Soviet (legislature) declared Nagorno-Karabakh to be part of Armenia. The Soviet authorities did not support the declaration, ruling it was unconstitutional. In September 1991 Armenian residents voted overwhelmingly to secede from the USSR, and the Armenian Supreme Soviet declared Armenia’s independence. The following month Levon Ter-Petrosyan, head of the Pan-Armenian National Movement and former chairman of the Armenian Supreme Soviet, became the first popularly elected president of an independent Armenia. The USSR officially ceased to exist in December.

Economic conditions in Armenia deteriorated rapidly in 1992. Azerbaijan’s economic blockade of Armenia, which closed both a railway link and a fuel pipeline, caused severe food and energy shortages throughout Armenia. Ethnic-based conflicts raging in Georgia also impeded delivery of urgently needed supplies to Armenia. Meanwhile, Armenian refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh and other parts of Azerbaijan flooded into Armenia, further straining the economy. In massive demonstrations in Yerevan in 1992 and 1993, Armenians protested the continuing energy crisis and demanded Ter-Petrosyan’s resignation.

In 1993 Armenian forces defeated the Azerbaijani army in several confrontations in Nagorno-Karabakh, which led to Armenian control of the region and of adjacent areas by August of that year. Although initial cease-fire agreements failed to hold, a new cease-fire agreement was reached in May 1994 after protracted mediation by Russia and the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe.

In July 1994 the political opposition to Armenia’s ruling party, the Pan-Armenian National Movement, staged anti-government demonstrations in Yerevan. Foremost among the opposition was the nationalist Armenian Revolutionary Federation, the same party that had established an independent Armenian state in 1918. The ARF strongly supported the Armenian secessionists in Nagorno-Karabakh, whereas the PNM maintained a somewhat distanced stance toward the secessionists. The ARF also rejected government efforts to introduce market reforms in the economy and opposed PNM-supported proposals for a new constitution that envisaged broadened powers for the president. In December 1994 the PNM-led government suspended the ARF, accusing the party of terrorism and other illegal activities.

In July 1995 Armenia held its first legislative elections as an independent country. The Republican bloc, a coalition led by the PNM, won a decisive victory to claim the majority of seats. The elections were monitored for fairness by the OSCE but were criticized by a number of opposition parties, which had been barred from participating. In a referendum held at the same time as the parliamentary elections, voters approved Armenia’s first post-Soviet constitution, which granted the president wide-ranging powers. In the presidential election of September 1996, Ter-Petrosyan was reelected to a second term amid widespread allegations of vote fraud. Popular protests against the election results escalated into violent clashes with police, followed by a crackdown on the political opposition.

In March 1997 Ter-Petrosyan appointed the elected president of Nagorno-Karabakh, Robert Kocharian, as prime minister of Armenia. Kocharian was a supporter of Nagorno-Karabakh’s ultimate secession from Azerbaijan. Ter-Petrosyan announced, however, that he was prepared to accept a compromise solution proposed by the international community, which would have left Nagorno-Karabakh formally within Azerbaijan but granted de facto control to the local Armenians. Ter-Petrosyan was forced to resign in February 1998 by hard-line supporters of Nagorno-Karabakh’s secession. One month later, Kocharian was elected to succeed Ter-Petrosyan. The status of Nagorno-Karabakh remained unresolved as of early 1998. Meanwhile, the cease-fire agreement of May 1994 continued to be maintained.

Text by: Ronald Grigor Suny for Microsoft Encarta

![]()

![]()