carriages of the

Simplon Orient-Express

for an excursion to Bath

the carriage awaits at Victoria Station

Welcomed aboard by the steward

into our carriage, the Perseus

for comfortable dining

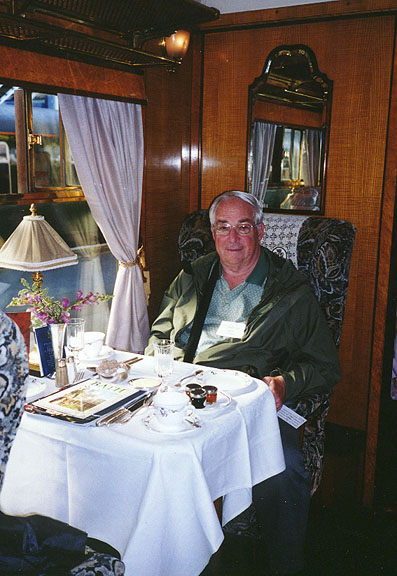

"The Traveler" ready for that dining

traveled along the Lower Avon river

to

Bath

Georgian atmosphere in a park like

setting

Royal Victoria Park and the Royal Crescent (1767 - 1775)

Bath (city, England)

, city and administrative center of the unitary authority of Bath and North-East Somerset, southern England, on the Lower Avon River. Long known as a health resort, the city has the only natural hot springs in Great Britain. Manufactures include printed materials, electrical equipment, and textiles. Tourism is also an important industry.

tourist street

with fancy shops

The University of Bath (1856) and the Bath Academy of Art (1946) are here. Points of interest in this elegant city include extensive remains of Roman lead-lined baths (discovered 1755), the Abbey Church (16th century), the Guildhall (1776), and the Pump Room (1796).

![]()

the Pump room (1796)

sampling the water

from the ancient Roman Bath

scene from the Roman city

Other Photos from Roman Aquae Sulis

The Roman town of Aquae Sulis was founded on the site of the springs in the 1st century. The baths were later abandoned, but by the 15th century the community was a center of the wool trade. During the 18th century, Bath became a fashionable resort; the layout of the city and its many fine Georgian buildings (including crescent-shaped blocks of town houses) date from that time.

Assembly Rooms

for dancing, playing cards, or drinking tea (no alcohol)

the assembly room hall now used as a costume museum

The city was severely damaged by bombing during World War II (1939-1945). Population (1994 estimate) 84,100.

Text from Microsoft Encarta

the Holburne Art Museum

crown in the square created for the Queen's 50th Jubilee 2002

![]()

Stonehenge in 1976

The Stonehenge that visitors see today is considerably ruined, many of its stones having been pilfered by medieval and early modern builders (there is no natural building stone within 13 miles [21 km] of Stonehenge); its general architecture has also been subjected to centuries of weathering. The monument consists of a number of structural elements, mostly circular in plan. On the outside isa circular ditch, with a bank immediately within it, all interrupted by an entrance gap on the northeast, leading to astraight path called the Avenue. At the centre of the circle is a stone setting consisting of a horseshoe of tall uprights of sarsen (Tertiary sandstone) encircled by a ring of tall sarsen uprights, all originally capped by horizontal sarsen stones in a post-and-lintel arrangement. Within the sarsen stone circlewere also configurations of smaller and lighter bluestones (igneous rock of diabase, rhyolite, and volcanic ash), but most of these bluestones have disappeared. Additional stones include the so-called Altar Stone, the Slaughter Stone, two Station stones, and the Heel Stone, the last standing on the Avenue outside the entrance. Small circular ditches enclose two flat areas on the inner edge of the bank, known as the North and South barrows, with empty stone holes at their centres.

The modern interpretation of the monument is based chiefly on excavations

carried out since 1919 and especially since 1950. Archaeological excavations

in the latter part of the 20th century suggest three main periods of

building—Stonehenge I, II, and III, the last divided into phases.

In Stonehenge I, about 3100 BC, the native Neolithic people, using deer

antlersfor picks (the carbon-14 dating of which has helped to date the

monument), excavated a roughly circular ditch about 320 feet (98 metres) in

diameter; the ditchwas about 20 feet (6 metres) wide and 4.5 to 7 feet (1.4 to

2 metres) deep, and the excavated chalky rubble was used to buildthe high bank

within the circular ditch. Twoparallel entry stones on the northeast of the

circle were also erected (one of which, the Slaughter Stone, still survives).

Just inside the circular bank they also dug—and seemingly almost immediately

refilled—a circle of 56 shallow holes, named the Aubrey Holes (for their

discoverer, the 17th-century antiquarian John Aubrey). The Station stones also

probably belong to this period, but the evidence is inconclusive. In addition,

a timber henge (circle) may have been erected at the site. Stonehenge I was

used for about 500 years and then reverted to scrubland.

During Stonehenge II, about 2100 BC, the complex was radically remodeled.

About 80 bluestone pillars, weighing up to 4 tons each, were erected in the

centre of the site to form what was to be two concentric circles, though the

circles were never completed. (The bluestones came from the Preseli Mountains

in southwestern Wales and were either transported directly by sea, river, and

overland—a distance of some 240 miles [385 km]—or were brought in two stages

widely separated in time.) The entranceway of this setting of bluestones was

aligned approximately upon the sunrise at the summer solstice, the alignment

being continued by a newly built and widened approach (the Avenue), together

with a pair of Heel stones. The double circle of bluestones was dismantled in

the following period.

The initial phase of Stonehenge III, starting about 2000 BC, was when the

linteled circle and horseshoe of large sarsen stones were erected, the remains

of which can still be seen today. The sarsen stones were transported from the

Marlborough Downs 20 miles (30 km) to the north and were erected in a circle

of 30 uprights (only 17 of which are still standing) capped by a continuous

ring of stone lintels. Within this ring was erected a horseshoe formation of

five trilithons, each of which consisted of a pair of large stone uprights

supporting a stone lintel. The sarsen stones are of exceptional size, up to 30

feet (9 metres) long and 50 tons (4,860 kg) in weight. Their visible surfaces

were laboriously dressed smooth by pounding with stone hammers; the same

technique was used to form the mortise-and-tenon (dovetail)joints by which the

lintels are held on their uprights, and it was used to form the

tongue-and-groove joints by which the lintels of the circle fit together. The

lintels are not rectangular, being curved to produce all together a circle.

The pillars are tapered upward. The jointing of the stones is probably an

imitation of contemporary woodworking. In the second phase of Stonehenge III,

which probably followed within a century, about 20 bluestones from Stonehenge

II were dressed and erected in an approximateoval setting within the sarsen

horseshoe. Sometime later, about 1550 BC, two concentric rings of holes (the Y

and Z Holes, today not visible) were dug outside the sarsen circle; the

apparent intention was to plant upright in these holes the 60 other leftover

bluestones from Stonehenge II, but the plan was never carried out. The holes

in both circles wereleft open to silt up over the succeeding centuries. The

oval setting in the centre was also removed.

The final phase of building in Stonehenge III probably followed almost

immediately. Within the sarsen horseshoe the builders erected a horseshoe of

dressed bluestones set close together, alternately a pillar followed by an

obelisk followed by a pillar and so on. The remaining unshaped 60-odd

bluestones were set as a circle of pillars within the sarsen circle (but

outside the sarsen horseshoe). The largest bluestone of all, traditionally

misnamed the Altar Stone, probably stood as a tall pillar on the axial line.

About 1100 BC the Avenue was extended from Stonehenge eastward and then

southeastward to the River Avon, a distance of about 9,120 feet (2,780 metres).

This suggests that Stonehenge was still in use at the time.

Why Stonehenge was built is unknown, though it probably was constructed as a

place of worship of some kind. Notions that it was built as a temple for

Druids or Romans are unsound, because neither was in the area until long after

Stonehenge was last constructed. Early in the 20th century,the English

astronomer Sir Joseph Norman Lockyer demonstrated that the northeast axis

aligned with the sunrise at the summer solstice, leading other scholars to

speculate that the builders were sun worshipers. In 1963 an American

astronomer, Gerald Hawkins, purported that Stonehenge was a complicated

computer for predicting lunar and solar eclipses. These speculations, however,

have been severely criticized by most Stonehenge archaeologists. “Most of what

has been written about Stonehenge is nonsense or speculation,” said R.J.C.

Atkinson, archaeologist from University College, Cardiff. “No one will ever

have a clue what its significance was.”

Stonehenge and the nearby circular monument of Avebury were collectively added

to UNESCO's World Heritage List in 1986.

Text from Encyclopedia Britannica

![]()

Return to European trains page

![]()